A unique opportunity to concurrently experience two exhibitions from two collections, exploring the same theme, providing an expansive and rich insight into the world of the MINIMAL in art.

LESS IS MORE

NOTHING IS SOMETHING

JAHM COLLECTION

MINIMAL: Less is More, Nothing is Something invites you to explore the elegance of restraint and the power of clarity. It celebrates the beauty of unadorned lines, the harmony of negative space, and the stories told through deliberate choices and quiet precision. It features works that invite contemplation, offering a serene escape from the noise of daily life.

This exhibition reveals the rhythm of simplicity in art that balances boldness with subtlety.

Don’t miss this transformative journey into the essence of art.

THREE THREADS OF ABSTRACTION

JARROD HABERFIELD COLLECTION

Abstraction was one of the key innovations in the art of the 20th century. While often discussed as a single movement, the truth of abstract art is far more diverse.

Three Threads of Abstraction is an exhibition drawn from the collection of Jarrod Haberfield and presents three series of works that illustrate Minimalism, Chromatic Abstraction and Mark Making… asking us to look closely, think deeply and see differently.

Minimalist art isn’t just something to see—it’s something to feel, something to experience.

Get ready to immerse yourself in the extraordinary power of simplicity.

LESS IS MORE, NOTHING IS SOMETHING

CURATORIAL ESSAY

Written by Charles Justin AM

Modernism in both architecture and art was defined by a process of reductionism that emphasised simplicity, clarity and the elimination of unnecessary elements.

In architecture, Mies van der Rohe, one of the giants of the modern movement coined the phrase ‘less is more’ to encapsulate the essence of modernist architecture. Its composition expressed by its core elements - function, structure, materiality and light, was coupled with the stripping away of ornamentation and historical references.

Similarly, modernist art progressively stripped away realism, representation and narrative, which led to various forms of abstraction expressed by the core elements of line, geometry, colour, form, space, repetition and materiality.

JAHM’s 2025 exhibition, MINIMAL: Less is More, Nothing is Something focuses on Minimalism, the next reductionist stage in the evolution of modernist art. Minimalism further stripped away personal expression and implied symbolic meaning. Minimalist artists asserted the primacy of the art object itself to be experienced by the viewer unmediated by the artist.

In many ways this concept of freeing up the viewer to determine meaning in a work of art coincides with Existentialism, the philosophy that places responsibility of creating purpose or meaning in our lives onto the individual and not external authorities.

Illustrated by works from the JAHM Collection, MINIMAL: Less is More, Nothing is Something will challenge the viewer to see how less can present more and what seems to be nothing can really be something.

THREE THREADS OF ABSTRACTION

CURATORIAL ESSAY

Written by Jarrod Haberfield

Then

In the first semester of my architecture degree I was taught Visual Communication by the wonderful Dutch artist Miriam van Wezel, who during class encouraged me to visit a local commercial gallery showing an exhibition of paintings by the Scottish minimalist Callum Innes. The suggestion was revelatory for two reasons: I didn't know commercial galleries were open to the public (I assumed you needed an invitation or a secret knock), and I had never encountered art before that seemed to achieve so much with so little.

Objectively, Innes’s canvases were short on content. There was a single solid colour, interrupted by one or two marks that read like scars, and it was challenging to decipher whether the marks had been applied over the colour or excised from it. Already at this stage of my architectural education I had learned about the positive / negative notion of figure and ground, but Innes made this dialectic impossible to comprehend. He made you step towards the work, and back again; he demanded rapt attention. Long before I would understand these works theoretically as abstract art, I knew the questions they were asking me to ask were not about people or places. The only person that interested the paintings was me. And the only place was here.

This early chance encounter catalysed a new kind of seeing for me. Viewed through a logical lens, it was obvious that there was little to comprehend, but the apparent absence of subject matter explained nothing of the thrall in which I was held. There was somehow so much to look at and I couldn't look away, and I swear there was an audible hum or vibration that emanated from the surface of the works like radio. It wouldn't be for many years later that I'd be able to draw connections from these Innes works to the paintings of abstractionists Ralph Hotere and Colin McCahon and Gretchen Albrecht that I'd seen during the museum visits of my youth, or to the magical landscapes of Aotearoa New Zealand in which I had grown up. In all these things there was a kind of thrumming silence – and still today it is precisely that thrum that suggests if an artwork is for me.

Now

The thinking for a mini exhibition of works from my collection was a kind of reaction to the theme of ‘Minimal’ on which Leah and Charles had already landed. If my PhD has taught me anything, it is the resistance of most things to conform to a singular reading. I grew up and was educated in a time when (and a place where) every system of thinking was presented and explained as a binary: good and evil, Caucasian and not, Christian and not, rich and poor, gay and straight. Even my university studies were replete with artificial binaries: local and global, historical and modern, truthful and decorative, architecture and building.

It is likely my developing mistrust of enforced singularity that attracts me to ambiguity in cultural production: my life in scholarship focuses on hybridity in architecture (both/and, not either/or), and my affections in art are reliably drawn to works that hover between concurrent or competing readings. I love drawings that look like photographs, and photographs that look like paintings, and documentary video that presents as digital fabrication. I'm increasingly comfortable with plurality these days, and I’ve settled into an acceptance that many truths can be true at once. Most things, it seems to me, exist on a spectrum – and so I sought to present here three (of many) threads of abstraction in the hope of complicating and enriching how a visiting public might conceive of ‘minimal’ art.

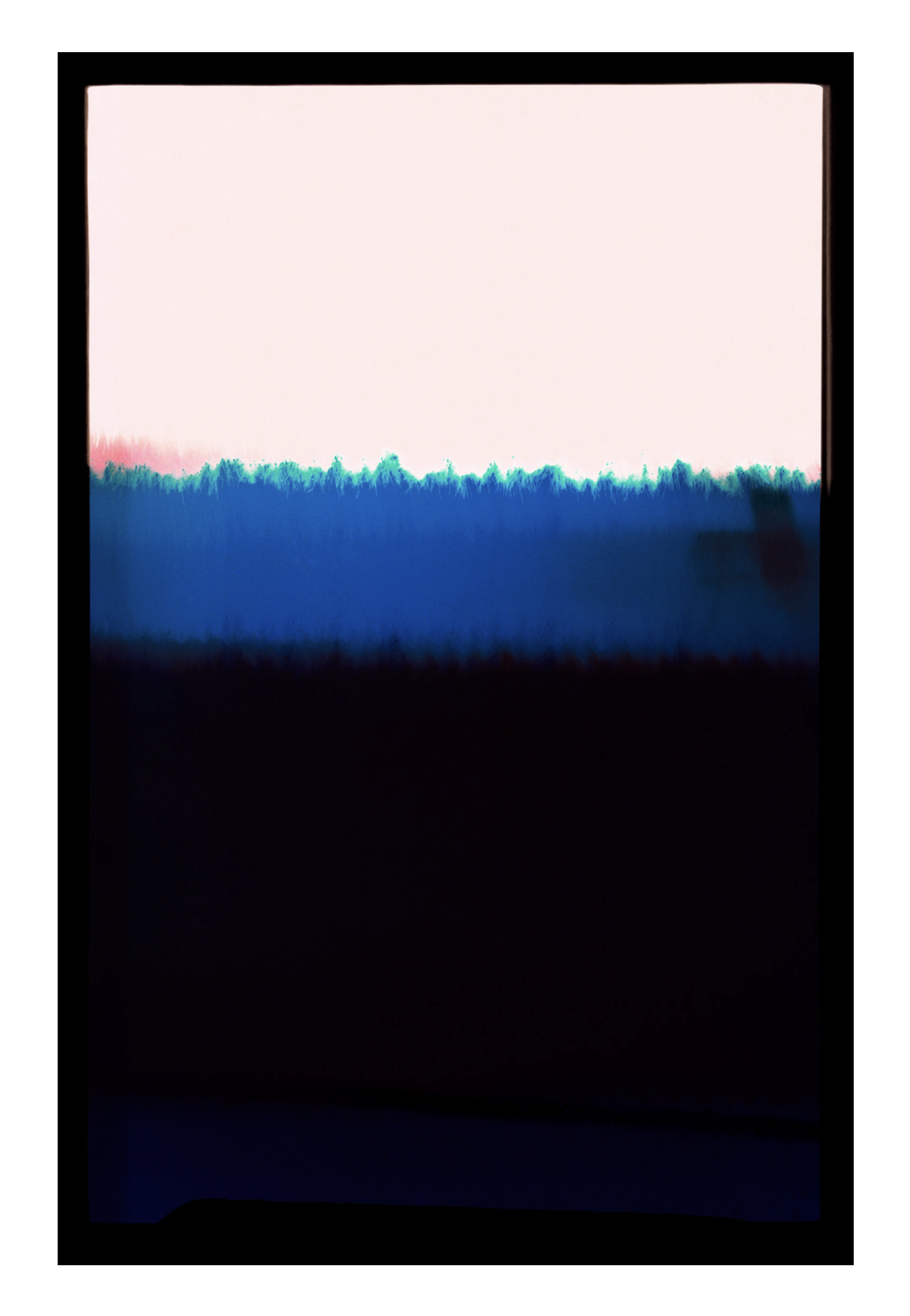

Minimalism

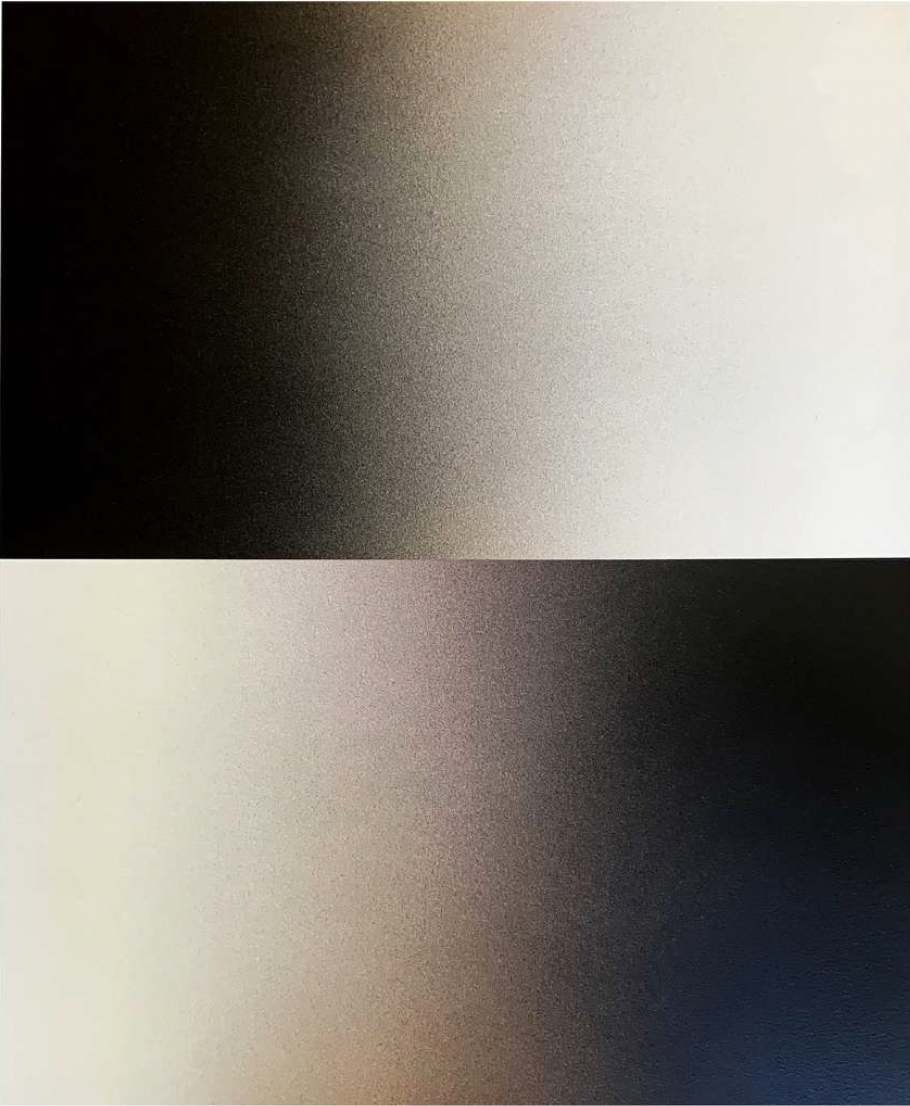

It was a shared love of minimalism that catalysed the early conversations between the Justins and me about my collected works appearing at JAHM. Minimalist art speaks to a deeper part of me than words can capture: since that first gallery visit there remains something thrilling about the dissonance between the apparent simplicity and the conceptual heft that sits in wait. The ultramarine monochrome of gouache on paper is the linchpin for this first ‘thread’ of works – of course for its sublime artistic quality, but mostly because it is the work of Callum Innes and provides for the narrative of the show a kind of full-circle resolution. Look closely and you'll see that two of the paper's edges are torn to reveal the layers of colour applied, and also that the rectangle of colour is rotated nearly imperceptibly against the paper. Photographs by Gary Fabian Miller, Robert Owen, and Daniel von Sturmer respectively betray our conventional expectations of a photographic image: a horizon bisecting ocean and sky of identical blues, the serendipitous beauty of the end of a roll of film and, unbelievably, a photograph of a shadow cast by a copy of Frieze magazine and printed faithfully at 1:1 scale.

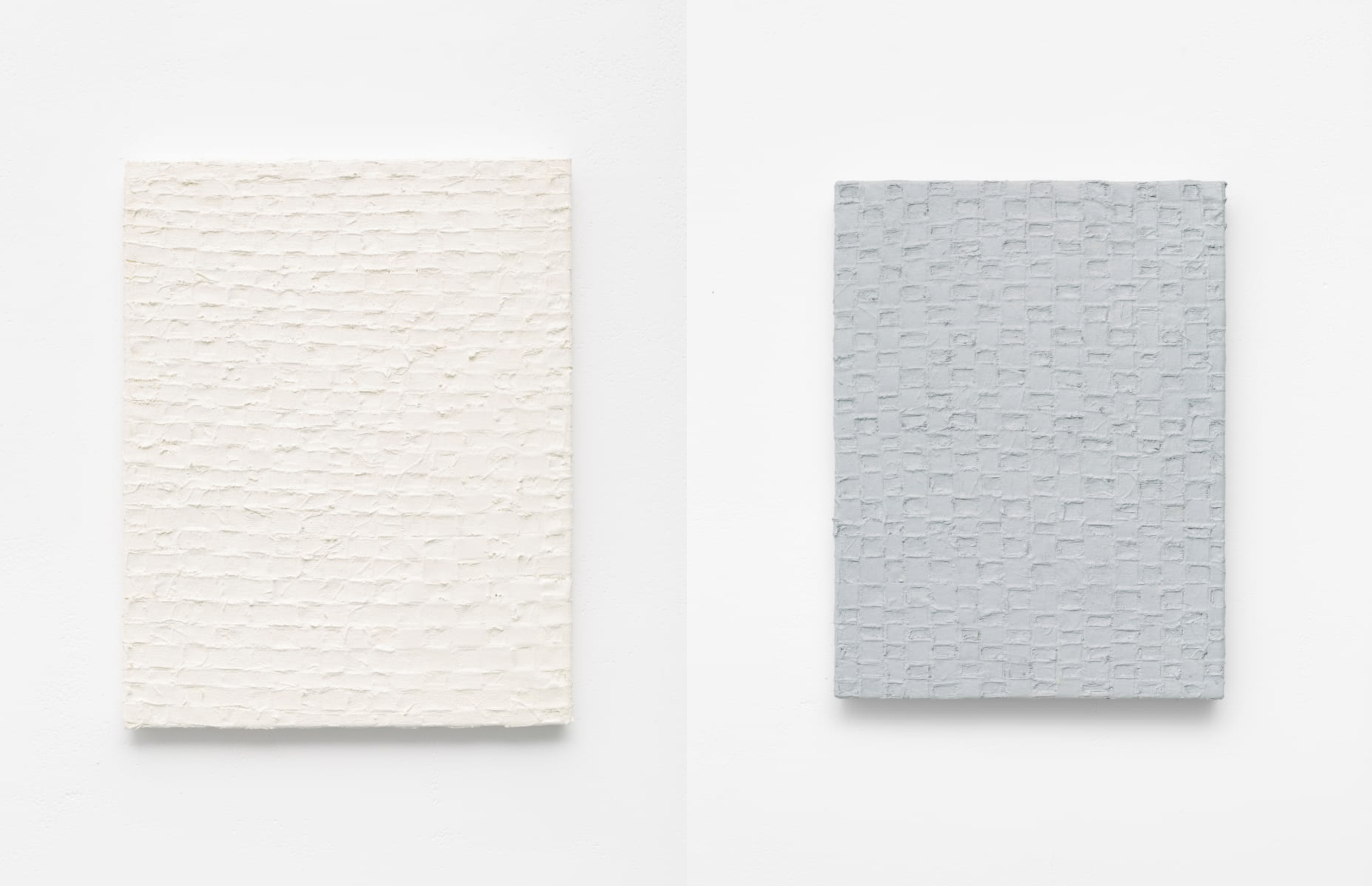

Von Sturmer's second work in this series is an airbrushed monochrome in silver, employing a curved perversion of the picture plane to create a kind of cyclorama and somehow trapping the surface between competing readings of draped fabric and stiffened metal sheet. The colour gradient that defines the curve has us asking whether the silver was achieved through additive passes of the spray gun or the white at its base revealed by erasure. The diminutive work that concludes this series is a riff on one of the most enduring abstract compositions of the 20th century – Josef Albers’ Homage to the Square. Artist Danica Firulovic commits a canny form of treason in the application of her signature whites, neutralising the very colours that endowed the original works with their historical significance.

Chromatic Abstraction

In deliberate contrast to the monochromes that line the wall opposite, the suite of works that comprises the Chromatic Abstraction thread of the exhibition deploy colour and geometric form as the bases for fundamental relationships and conversations within each frame and, in several cases here, between frames. Theoretical discussions of colour and colour theory are much better left to two of the featured artists – Dr Anna Finlayson and Dr David Sequeira – whose practice-based doctorates focused on exactly these issues. Both Finlayson’s and Sequeira’s practices engage with seriality, a sense of an ongoing exploration of a question with infinite answers.

Finlayson’s works are selected from two series, and each feels to me like a page torn metaphorically from a sketchbook. Graphite notations and musings appear superimposed onto arrays of meticulously applied smudges of paint – there’s a sense of a timelapse of process and final product that has somehow folded in on itself. Sequeira’s works from his ongoing Songs series make explicit the links between colour and sound of which I’ve spoken. Musical staves are deployed as an organising framework for the freehand geometries applied, and comparisons are unavoidable to the musical form of Variations on a Theme.

While all the chromatic works seen here exhibit a kind of boldness by virtue of rigorous composition and glorious colour, each also exhibits incredible control – in fact, they illustrate perfectly my favourite definition of minimalism that I heard years ago: a state of resolution in which nothing more can be removed without injury to the reception of the work. Completing this wall, Max Lawrence White and Michael Hourigan prove in their works the powerful relationships made possible in the juxtaposing of reductive geometries and judiciously chosen colours. Both White’s single canvas and Hourigan’s tetraptych demonstrate to my mind a tightrope walk between repose and rebellion.

Mark Making

The five works that comprise the Mark Making thread of the show are notable for their diversity, but they have in common an ambiguity of which I spoke earlier. The vast unprepared canvas of Hugo Koha Lindsay presents as a rapid application of painted roller strokes. (Comparisons with Abstract Expressionism or Action Painting are unavoidable.) We are instead dealing with a monotype print, created by the application of paint directly onto the studio floor and a single, risk-laden pressing of the stretched canvas to receive the still-wet paint. Small roundish marks are visible amongst the curvilinear strokes – these are imprints of Lindsay’s knees and wrists as he crawled his way across the canvas to ensure the contact of the print.

Idris Khan's work appears straightforwardly as a chalk drawing on blackboard; the Cy Twombly reference is explicit. We are instead looking at a composite image of hundreds of Khan’s own drawn scribbles, which he photographed in turn and then layered digitally to create the artefactual image. Watiyawanu artist Lily Kelly Napangadi has spent her life recording the landscapes of her Country using white dots on black canvas. With the subtlest shifts in dot size, contours and typographies emerge. Here, we are above the land and within it all at once – the ultimate depiction of space-time that European modernists thought they invented, and which Aboriginal Australians have been painting all along. Recalling my earlier comments about audibility, Napangadi’s works transmit an unmistakable vibration. The smallest work of the show is Nick Berry’s jewel of a painting, which is delightful for the discernible traces of its production. There's no sleight of hand here – unlike the ambiguity of Lindsay’s ‘painting’ or Khan’s photograph, here we enjoy the sensuous application of metallic gold paint on black canvas one legible gesture at a time, shimmering between liquid and solid states in perpetuity.

This thread and the exhibition’s arc conclude with Leela Schauble’s Signals, the only time-based work featured in the show. Schauble’s video presents as a digital manipulation in which orb-like flashes of light are animated as a superimposition over a still image. We are in fact watching documentary footage of icescapes in the Arctic Circle studded with mountaineers’ lamps set to the Morse-code sequence for SOS. The melting ice stands in as a proxy for a planet in crisis, and Schauble’s flashing lights call silently to the viewer for help.

Look, Think, See

It is a thrill for me to witness this selection of artworks re-presented in a new setting for a new audience. These works have been acquired over the last 15 years, and each has a story and a specialness that’s become somehow enmeshed in my own identity. My hope is that when considered in concert with the Justins’ wonderful exhibition on the level below, visitors to JAHM will have enjoyed a series of windows through which abstract and minimal art might be seen and understood. Minimal art in all its guises rewards curiosity – about the artist’s practice broadly and process of making specifically. While minimal artworks are easily lampooned and dismissed as superficial, this exhibition will hopefully galvanise an appreciation that in the best versions of minimal art, a seemingly simple aesthetic belies rich and layered thinking. You are invited to look closely and think deeply. And if you’re lucky, you’ll leave seeing with a new set of eyes.

© Jarrod Haberfield, February 2025

STAY CONNECTED

Be sure to keep up with all JAHM updates and Australian exhibition highlights by connecting to our socials. And if you haven’t already, subscribe to our mailing list to receive newsletters with all details of upcoming programs and tours at JAHM.