DIVINE ABSTRACTION

3 April - 19 June 2016

Curated by Charles Justin and Dr. Rachael Kohn

Can abstract art represent the abstract Divine?

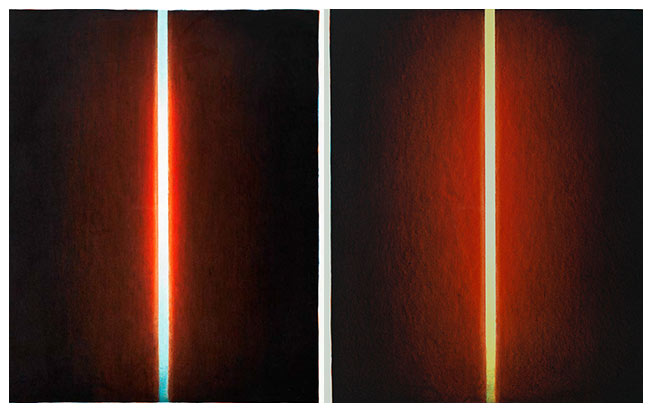

JAHM’s inaugural exhibition features 18 works from our contemporary art collection that includes videos, digital works, photographs and paintings. Each abstract artwork describes a manifestation of the divine and collectively the exhibition presents a picture of the Divine that on the one hand is ephemeral, but on the other, can be a profound ingredient in our human lives.

Renowned ABC broadcaster and writer Dr. Rachael Kohn, regarded as one of Australia’s pre-eminent authorities on theology and spirituality, has written a critical overview of the exhibition and an insightful series of essays on each of the works.

The Divine Abstraction exhibition presents a proposition that art can provide as powerful a pathway in our search for meaning, as does religion and philosophy.

JAHM SESSIONS

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

CURATORIAL ESSAY

Abstract Divine in Art

Catalogue essay by Dr Rachael Kohn

The Moderns who coined a new sacred language

Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) the author, poet and critic, prophetically described the artist’s contribution to a new metaphysical language when he wrote of the cubist art of his day, which “borrowed not from the reality of sight, but from the reality of insight”.

A century later the relevance of this statement could not be more evident. As the West’s third-millennium culture drifts ever further away from the richly illustrated fables, myths and narratives that are foundational to its religious traditions, so it becomes less and less able to discern their meaning and ascent to their truth.

Although the public still flocks to exhibitions of the great masters, whose works are often dominated by Biblical themes, the majority is drawn more to the reputation and brilliance of the famed artists than to the stories they depict. Most of the religious references the paintings contain are lost to the typical viewer, who is reliant on the popular thumbnail descriptions provided to them via audio guides.

Yet, with the loss of conventional belief, as in Apollinaire’s time, a new type of art has stepped into the breach to communicate divine realities, which are intuited if not seen. From sight to insight implies a move from exterior realities to interior ones, from imposed dogmatic formulas and creeds to the individual’s mystical experience of the source of all reality.

Apollinaire believed not only that the cubists rendered the essential reality “with great purity,” but that “all men have a sense of this interior reality”.

Purity, essence and the democratization of spiritual knowledge are salient features of today’s religion for the non-religious, and art serves as its audacious and often surprising symbolic language.

Some however might imagine that this is a purely accidental state of affairs, that is, abstract art has replaced pictorial art (for any number of reasons) and the public is left trying to imagine spiritual profundities in the largely blank or confronting canvasses. After all isn’t that what one is expected to do?

While people may indeed strain to find spiritual meaning in abstract art, it is only for want of knowing what the modernists intended, for they frequently wrote of their spiritual aspirations.

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) for example, who gave us the most distinctive architecturally inspired designs, dominated by black framed squares, surrounding bright red, white and yellow hues, in contained yet exuberant canvasses, is most often recognized as the catalyst for an industry of decorative imitations.

Yet the Dutch-born, Paris-based Mondrian pursued a universalist ideal, and wrote of “the universal–although it is a gem within us–towers far above us; and just as far above us is that art which directly expresses the universal.” Far from being a mere painter of pleasing designs, Mondrian saw himself engaged in a search for meaning as profound as and comparable to religion:

“Art, although an end in itself, like religion, is the means through which we can know the universal and contemplate it in plastic form.”

The twin functions of art are unambiguously stated as both an end in itself and as a vehicle for spiritual enlightenment. Indeed, Mondrian’s philosophical reflections on the meaning of art are complex and often turgid, influenced by German idealism and a theosophical conviction that man was spiritually evolving away from physicality, individuality and the ego, and toward “a new culture” where “the individual will be open to the universal and will tend more and more to unite with it.”

Mondrian was but one of an international array of artists drawn to Cubism and subsidiary artistic movements in the early twentieth century, but it is a form that is often misunderstood by the casual viewer. Cubist canvasses can seem a mere assemblage of playfully dismembered parts, akin to a child who pulls apart his toys and puts them back together in no particular order.

Tempting as it might be to think of cubist portraits in this way, one could hardly say this of Georges Braque (1882-1963), for example, who explained his paintings to a journalist by admitting that he was simply unable to convey a woman in all her natural loveliness.

“I must therefore create a new sort of beauty, the beauty that appears to me in terms of volume, of line, of mass, of weight, and through that beauty express my subjective impression…I want to expose the absolute and not merely the factitious woman.”

Like Mondrian, who imagined the ideal artist as a humble interpreter without ego, so Braque also willingly admitted to being unequal to the task of recreating exactly what he saw in nature. Instead Braque aspired to capture the underlying essence of nature, what Mondrian referred to as the mystical forces that governed the universe.

Forces give way to forms, which in a circular fashion point back to the ultimate force underlying all life. Nowhere was this relationship more starkly presented to the viewing public than in the Russian avant-garde painter Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, painted in 1915 and presaged in his 1913 costume and prop designs for the futurist opera Victory Over The Sun.

The tilted black square floating on a bed of white was an audacious minimalist statement that gave birth to decades of canvasses, especially by post-war American artists, of geometric forms in striking juxtapositions that hinted at a supra-objective reality, which Malevich called ‘suprematist.’

“This strange word,” writes Frances Spalding in The Guardian, July 2014, “derives from supremus, meaning “superior” or “perfected”, and refers to Malevich’s intent to liberate painting from the shackles of mimesis and representation, to raise it to a higher state and into greater spatial freedom.”

One might say a greater spiritual freedom as well, for Malevich believed that humanity was on the brink of a new spiritual age that would replace the world of familiar objective reality, like the icons of his Eastern Orthodox tradition. And so it was fitting that when Spalding visited the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow in 2014 he spied Malevich’s Black Square, a relatively small painting, positioned high up and in a corner of the room. To the untrained viewer that curious location might seem like a banishment.

“But the use of a high-up corner space also evoked the sacred,” observed Spalding, “for it was precisely where an icon usually hung in the traditional Russian home.”

There in the Moscow gallery, which had hidden the Black Square from view for 40 years during the period of state-imposed socialist realism in art, Malevich was finally allowed to replace the old iconographic tradition with a new one:

“Amid the visual clamour elsewhere in the museum, it acts like a sudden silence.”

That mood of contemplation and introspection, which Spalding, the contemporary art critic, sensed was exactly what the artist intended, but in his time Malevich had to weather the withering criticisms that Black Square provoked, especially when he followed it with a white square, titled Suprematist Composition: White on White (ca 1918).

Undaunted, the true believer in him pressed on, in both his painting and writing, determined to avoid the trap of nostalgia and “likeness of reality”, and commit to experiencing the terrifying mysterium tremendum of an encounter with the absolute. In his flat squares of black on white and white on white, Malevich invested the promise of transformation, akin to the mystic’s quest in the desert.

“But this desert is filled with the spirit of non-objective sensation which pervades everything.

Even I was gripped with a timidity bordering on fear when it came to leaving ‘the world of will and idea’ in which I had lived and worked and in the reality in which I had believed.

But a blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity drew me forth into the ‘desert’, where nothing is real except feeling…and so feeling became the substance of my life.”

There is an anarchic impulse in the desire to live by feelings alone and be rid of forms, which Malevich expressed in 1918, when he called for humanity to “clean the [town] squares of the remains of the past…clean yourselves of the accumulation of forms belonging to past ages.”

A call to action for the born revolutionary, however, was but a philosophical truism to the wry observer, Paul Klee, (1879-1940), the witty Swiss artist who represented the height of the Bauhaus movement (1923-1933). Although both artists regarded the world of objective forms as secondary to their abiding spiritual essence, Klee, writing in his notebooks, saw the artist’s identification with the absolute as an inevitability.

“Everything passes, and what remains of life, is the spiritual. The spiritual in art, or we might simply call it the artistic. In everything we do the claim of the absolute is unchanging.”

Equating the artistic impulse with the absolute, giving it something like a divine imprimatur, might be a touch of the satirist coming through in Klee’s at times obtuse journal entries, but in this entry from his notebooks Klee nonetheless waxes almost Biblical about the power and import of artistic creation:

“The power of creativity cannot be named. It remains ultimately mysterious. What does not shake us to our foundations is no mystery. Down to our finest particles we are charged with this power…Creation lives as genesis invisibly under the surface of the work.” (192)

In contrast to the Biblical language of creation in which every artwork is a new Genesis, the symbolic language of circles and triangles which crowd the later works of the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) while he was living in Paris, speaks of his interest in the esoterica of ‘spiritual science’ and Kabbalistic diagrams and ideas.

In fact, Kandinsky, who earlier in his artistic career was inspired by the last book in the Christian Bible, the Book of Revelation, later developed a highly complex spiritual art theory that incorporated music and colour (synesthesia) and mathematical formulas, which he published as Du Spirituel dans l’art (The Spiritual in Art) in1912.

Kandinsky, above all, believed that abstract art revealed the spirit: “The more obvious is the separation from nature, the more likely is the inner meaning, to be pure and unhampered.”

How much do these works of art, and especially Kandinsky’s beguiling kaleidoscopic canvasses, communicate their spiritual messages unambiguously? Is the viewer actually prevented from deciphering their hidden meaning if the writings of the artists themselves are not read and studied alongside their works? One must honestly answer to a large extent in the affirmative.

And yet today, the heirs of these pioneering artists have a far less urgent need to write treatises justifying and explaining their visionary canvasses than did their forebears, ‘the moderns,’ who laid the groundwork for them. By contrast, today’s artists freely borrow from the arsenal of architectural geometry, mathematics and photography, computer graphics, genetics and cosmology, all of which, and much more, have become normative features of our technological culture and our scientific knowledge of the world.

Meanwhile, the interior spiritual quest, which is no longer necessarily or exclusively tied to particular religious narratives, but intuits a transcendent source of life and wisdom behind them all, has become a widely accepted expression of contemporary belief and consciousness.

Abstract art, which ranges from the quietly cryptic to the shockingly bold, is in many ways the most appropriate language for today’s fluid spiritual milieu, which is mutable and often highly personal. Indeed, far being fixed, today’s spiritual quest begins with an open-ended agnostic stance and continues on an adventure in need of new ways of expressing ‘the grandeur of metaphysical forms,’ as Apollinaire predicted, and I would also add the profundity of personal existential spiritual experience.

Perhaps the manifold symbolic representations of metaphysical and cosmological grandeur have become spontaneous and intuitive, rather than deliberate and studied, which may indicate that we have reached a stage of spiritual evolution in our Western culture where the artistic language of the ‘abstract divine’ has become a recognised sacred tongue.

Contemporary artists whose work suggests the Abstract Divine

What remains an open question, however, is whether the contemporary art we view today can prompt spiritual insights and questions beyond or even in spite of the artist’s stated intention. In this selection of artworks that comprise the first JAHM exhibition, the answer is definitely affirmative.

Each artwork is strongly suggestive of key elements of the abstract divine, demonstrating the power of art to communicate transcendent ideas and tap into the deep recesses of our shared cultural, psychological and religious consciousness.

Not only do they harken back to the spiritual ideas that propelled modern art into contemporary culture, and were constitutive of its symbolic language, but they also demonstrate how contemporary works can employ archetypal symbols drawn from many religious traditions and act as fresh stimuli for the viewer’s unique spiritual insights.

“The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known,” wrote Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984), the Russian and Soviet literary theorist who actually provided a theory of art that speaks to this contemporary situation, even as it did in 1917 when he coined the term defamiliarization (ostranenie).

“The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object; the object is not important.”

The perpetual open-endedness of the art object, suggested by Shklovsky, which favours the viewer’s perception and emotional reaction and prompts a struggle to decipher its meaning, is exactly what makes abstract work an appropriate vehicle for the divine transcendent.

All mystics, from the Buddha to Hildegard of Bingen, from Isaac Luria to Swami Vivekananda and beyond, and even philosophical rationalists like the medieval masters of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, respectively, Moses Maimonides, Thomas Aquinas and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), agreed that the divine transcendent (in conventional terms, God) could never be contained, delimited, objectified, described or pinned down, and could only ever be known in partial terms and from a human point of view.

The struggle to discern and decipher the divine presence, goes all the way back to the Biblical legend of Jacob, whose all night struggle with a shadowy angel is widely interpreted as his struggle with God, as indeed he saw it: “I saw God face to face, and yet my life was spared” (Genesis 32:30).

The eighteen works in this exhibition by contemporary artists contain elements and qualities, archetypal images and scientific data, received ideas and open-ended questions that prompt reflections on the divine transcendent.