ART & GENDER

February 2022 - November 2022

Gender is an issue today that is both topical and complex. At JAHM, we are presenting works drawn from our collection, as a vehicle to explore the nature and processes of the artwork and to consider whether the artwork reflects the gender of its artist. By interrogating the practices and works of some of the 60 artists represented, we hope to stimulate conversations and insights into the influence gender has on the creative outcome and examine and reveal our own embedded biases.

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Photography by James Morgan

CURATORIAL ESSAY

Charles Justin AM and Leah Justin, Justin Art House Museum

What relevance does an artist’s gender have on the work that they create? If you regard the work of an artist as a manifestation of their persona, you will think it is critical. But why only gender? Aren’t there other factors in an artist’s identity such as race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, culture, education, economic, which might influence in some way, who they are and what they say. Nonetheless gender seems to be a prominent characteristic, as evidenced by the major exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia that ran in 2 stages over 2020 and 2021. Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now. This exhibition showcased over 250 Australian women artists in one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of its type and was in response to the long-held criticisms to the historic under-representation of women artists in public museum collections and exhibitions.

To understand its relevance, perhaps we need to define what we mean by gender? Are we only talking about men and women?

Our Gen X daughter, reminded her ageing baby boomer parents (us) that today we recognise that there are more than two genders, which she reinforced by sending us the gender categories on the current Victorian COVID vaccination forms. The choices listed were manifold - Female, Intermediate, Intersex, Male, Non-binary and Unspecified. Gender identity today is complex and in addition to male and female, also includes lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, trans-sexual, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) as well as gender diverse and gender fluid. Although difficult to measure, it is estimated that the percentage of the population that is LGB is 3-4%, trans is 1% and intersex is 1.7%. One would expect that in a liberal, democratic and pluralistic society the rights, needs and concerns of all minorities need to be recognized, which would apply equally to the LGBTIQ community. Today this is very much in the forefront in the battlelines of liberals and conservatives over the ‘woke’ agenda.

Nonetheless as the vast majority, of over 90% of the population, identify as male or female, this is where we have decided to focus our exhibition ART & GENDER. Our approach in an area so complex is that by reducing the variables to male and female, it will allow us to deepen our focus in our exploration of creativity and its relationship to gender. To that end we have canvassed all the artists in our exhibition on their preferred pronoun - he/him, she/her, they/them and 100% of the responses were either he or she, except one which on principle was non-committal.

The first artwork acquired in the JAHM collection in 1973 was Phantom Scenes by Lorraine White, which is included in this exhibition. We purchased it from a highly respected gallery at that time, Gallery A in Toorak Rd. We bought the painting because we loved it and we still do. Although we were aware the artist was female, it played no part in our decision and it hasn’t influenced any of our choices to this day. Lorraine White died with her work mostly unrecognised and as an artist she is pretty much unknown. The question looms about the trajectory of her career as a female artist.

2021 saw the publication of Doing Feminism: Women’s Art and Feminist Criticism in Australia by Anne Marsh. With 544 pages, 370 colour illustrations and representing 220 artists, it is one of the most comprehensive collections of material on women and the arts in Australia. The work traces, decade by decade, since the 1960’s, the development of women’s art practice, exhibitions, critical thought, highlighting the struggles and limitations women artists endured, particularly in the early years. It would be fascinating to understand the cause of attrition of the women artists like Lorraine White who fell by the wayside. Was it lack talent, lack of drive, lack of connections or was it being a female artist in that era? Had she been a male artist would her career as an artist have been different? Of course why one artist succeeds, and another languishes - is a question that exists in all spheres of the arts and in life in general. Gender may not be the reason, but it could readily be a reason.

We came to the realization some years back that our art collection of over 300 works is pretty evenly split between artists we perceive as male or female. This wasn’t an objective of our collecting practice, but an outcome. We found this to be revealing. Our decision making was and is always based on the merit of the work itself, without consideration of the gender of the artist. Yet remarkably this has resulted in our collection mirroring the distribution of male and female genders within general society, this in itself is saying something.

This became the seed of an idea for an exhibition at JAHM based on the works in our collection. Perhaps it would be worth exploring if or in what way the gender of the artist influences the creative outcome. At JAHM we don’t have wall labels for the works, so for the majority of our visitors the gender of the artist will be unknown. Our intent is not to categorize artist as male or female, but to utilize this division as a mechanism to explore what influence, if any, gender makes. The exhibition’s construct is to pair works by male and female artists, with the pairing based on some element that ties the works together. This could be subject matter, artistic practice, idea, materiality, historic reference, allusion etc. Hopefully this will provide a platform to interrogate the works, examine what they have in common and how they differentiate themselves and then generate a discussion on whether the work reflects characteristics of masculinity or femininity.

But of course, to do so we need to understand what those distinctions of male and female might mean?

The starting point in our undertaking is to acknowledge the obvious - males and females are different. Biologically they have different chromosomes (XY for males and XX for females), different genitalia both external and internal, different gonads (testes for males and ovaries for females), different levels of hormones (higher testosterone for males and higher oestrogen for females), males tend to be bigger with a higher muscle percentage as well as higher levels of facial and body hair, females have larger breasts and hips and higher body fat percentages. If form follows function, the evolutionary process that designed the male and female machine did so for females to give birth, nurture and rear their young and males to provide for and protect them.

Many of the characteristics and behaviours that are attributed to males and females flow from these primal roles that they have fulfilled since the beginning of humanity. Consequently males are considered more aggressive, more competitive, take greater risks, are more action orientated, are more impulsive, more impatient and easily bored, excel in spatial skills which leads them to be better at mathematics, physics, economics and 3D thought processing, more suited at doing one thing at a time. Females on the other hand are considered more empathetic, caring, conciliatory and collegiate in the way they operate, are more verbal and have better communication skills, better at managing detail, better at multi-tasking, better at hearing, have a larger colour vocabulary and have greater finger dexterity.

Whether the above male and female characteristics are the result of nature or nurture is of course an ongoing vigorous debate. There is research to support that the above attributes are wired into the male and female brains, however the opposing school of thought is that these attitudes are shaped by historical precedent in the way males and females roles in society have been structured and the way people’s attitudes have been shaped by their upbringing and education in a male dominated society. Nonetheless there is NO evidence that precludes males or females in excelling in areas outside their perceived core strengths or for example, suggesting that females can’t be soldiers or that males can’t be carers.

Again, the above categorizations could be regarded as gender stereotyping, which is the practice of ascribing specific attributes, characteristics or roles to a gender that is used to disadvantage that gender. But it could also be used to explain the different way that males and females operate, which when misinterpreted or misapplied, causes disadvantage. As a real life example, for people who don’t consider art as serious, in the largely male dominated business world today, only 6.2% of CEO’S are female. It appears that the business world considers the male attributes of aggression, competitiveness and risk taking as the necessary prerequisites to be a successful corporate leader. However, research has shown that appointing a female CEO can increase the market value of the ASX listed company by 5%. Obviously, their strengths in team building, strengthening corporate culture, collegiate thinking, better communications and multi-tasking provide an effective alternate model to corporate management. What this demonstrates is that one size doesn’t fit all and that different approaches to challenges can be equally successful. Difference should be celebrated.

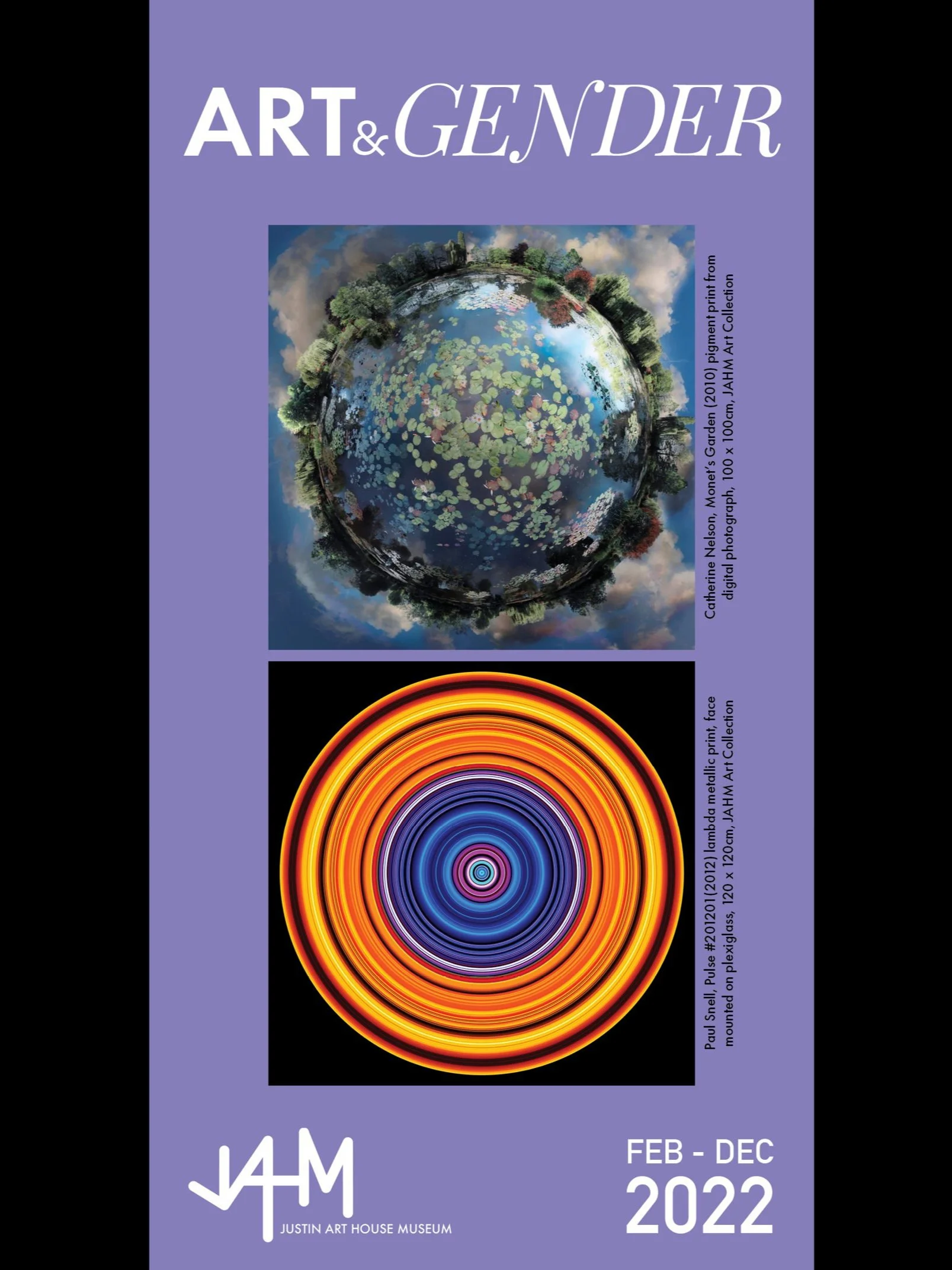

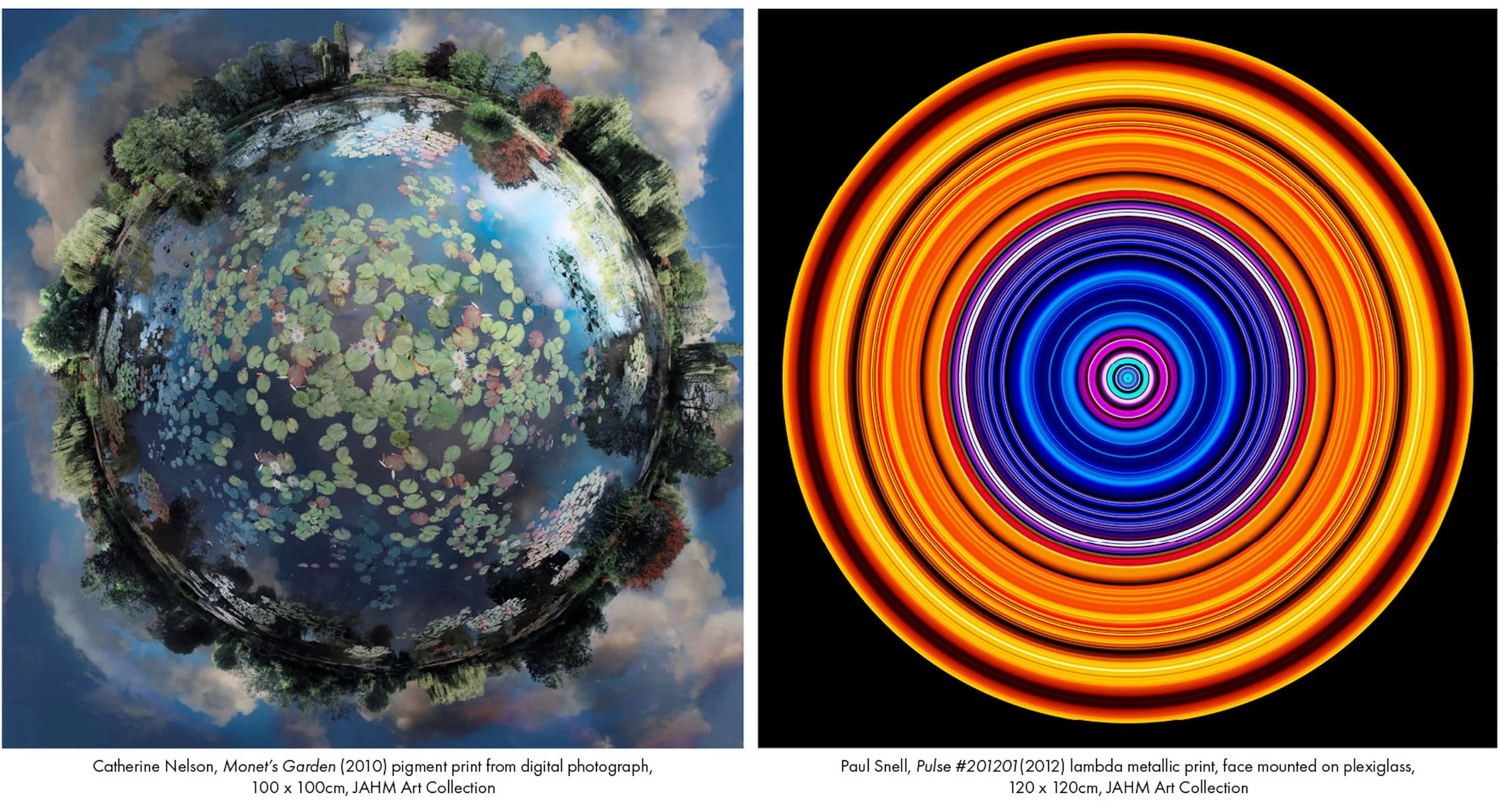

Let us look at one of the pairings in the exhibition that we are using in the promotion of ART & GENDER. One work is Monet’s Garden (2010) by Catherine Nelson, the other Pulse (2012) by Paul Snell. How are they different and how are they the same? Both works utilize digital technology in restructuring photographic imagery into an alternate image. Catherine Nelson walked around Monet’s garden in Giverny outside Paris, progressively photographing over one day, the lake and the gardens in about 1000 images. She then digitally stitched these separate photographs into a single seamless image of the garden expressed as a globe floating in space. The final result was not an attempt in representing the garden, but was the artist’s fantastical impression of the garden. An impression of an impressionist’s garden. Paul Snell appropriates photographic images from the internet and manipulates them digitally to create a totally different image. The new image is abstract with no reference to the content or representation of the original image or images. The new image is a distinctive geometric abstraction, with a series of bright coloured concentric circles that project a pulsating energy. Does the fact that Nelson’s work is a landscape with allusions to Mother Earth which has been transformed into a vision of an earthly paradise, display feminine qualities. Alternatively, does Snell’s work which is highly abstract, high energy, with its bulls-eye geometry display masculine qualities. Perhaps the exhibition will not only be an exercise in attempting to understand the artists’ influences but also the viewers confronting their own gender prejudices. That remains to be seen.

Finally is this exhibition ART & GENDER simply a conceit? Is the prospect of selecting from a personal art collection reasonable, as it is so highly subjective? Is the prospect of looking at 32 pairs of works by male and female artists with the objective to explore gender in art even realistic? Hopefully there is sufficient diversity in the works to introduce some degree of objectivity. We hope it will raise issues, generate conversations and open discussion on what is a complex and often highly charged topic. Being a small, privately run institution, we can afford to take risks and celebrate difference.