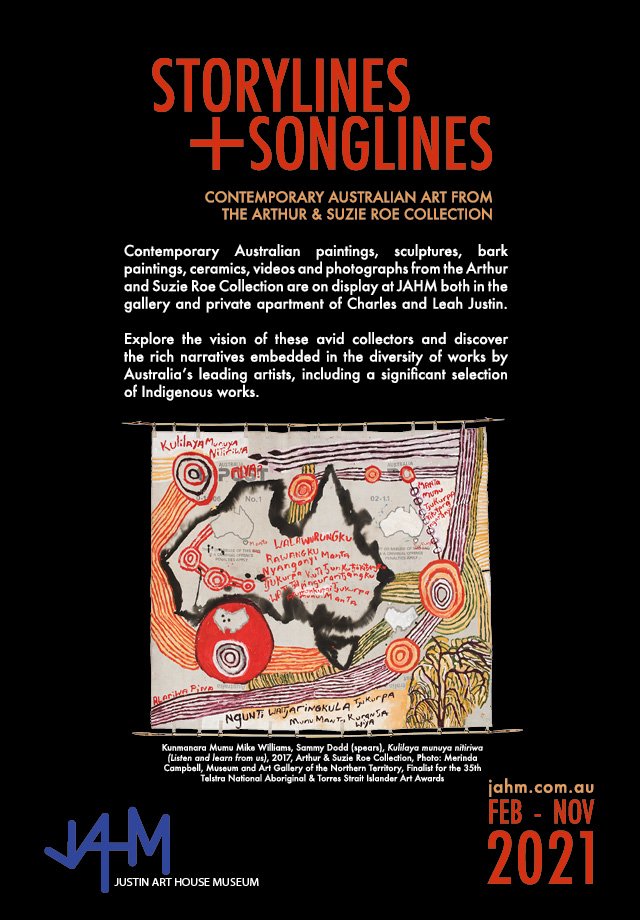

STORYLINES + SONGLINES:

Contemporary Australian Art from the Arthur and Suzie Roe Collection

February 2021 (thanks COVID) - November 2022

What does contemporary Australian art look like? Is collecting creative, philanthropic, or just an addiction? What do artworks tell us about our world and the worldview of the artists?

The current JAHM exhibition, Storylines and Songlines showcases an impressive selection of contemporary Australian paintings, sculptures, bark paintings, ceramics, videos and photographs from the Arthur and Suzie Roe collection.

Journey into the minds of these avid collectors and experience works created by some of Australia’s leading artists.

JAHM SESSIONS

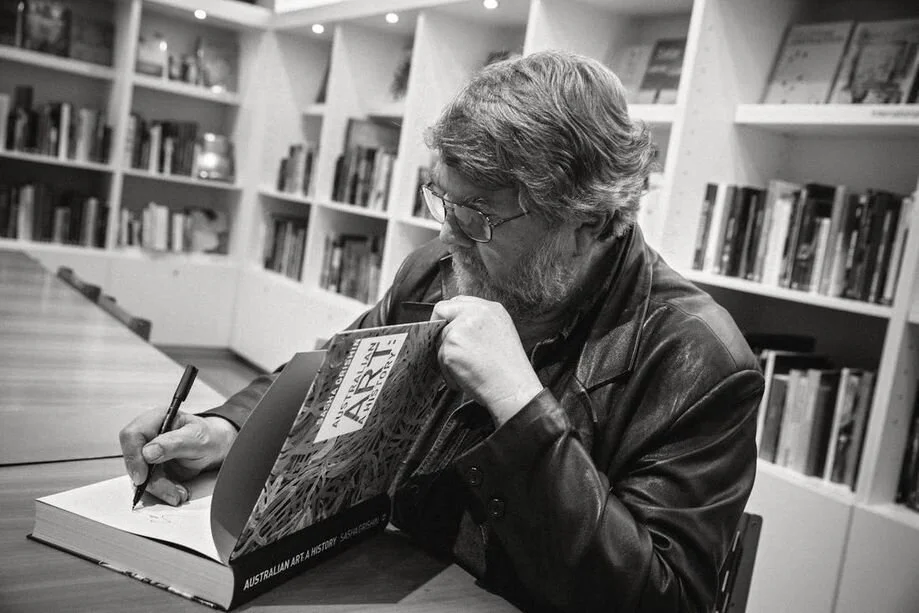

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

CURATORIAL ESSAY

Emeritus Professor Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA

Australian National University

The traditional discourse surrounding Australian art advocated for the structure of apartheid, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian artists were separated and segregated into two separate traditions. Although this has been challenged in some of the more recent publications on Australian art history and in the integrated displays of Australian art in some public art galleries, especially the National Gallery of Australia, the old demarcations remain in place in many quarters.

The Arthur and Suzie Roe collection, amongst a number of other private contemporary art collections, does away with boundaries between Indigenous and non-Indigenous art and views contemporary Australian art practice as a single multifaceted entity, where it seems to make little sense to create separate ghettos for art of different racial and ethnic origins. One can argue that Aboriginal art had a direct impact on the art of the First Fleet artists and Indigenous art has continued to have an impact on non-Indigenous Australian art, to a greater or lesser extent, through to the present. This is not a question of assimilation or integration, but an ongoing dialectic, almost like a game of Ping-Pong, where ideas between artists bounce off one another. It would be silly to bring out the colonial concept of ‘authenticity’, that somehow the purity of art is contaminated if it learns from other traditions. This notion that a great tradition in art is only authentic if it is fossilised in noble isolation belongs to the realm of tooth fairies, a living tradition of art survives in a state of flux and development and it is this that gives it vitality and its continuing authenticity. Reciprocally, Indigenous art also accommodates non-Indigenous aspects of art, whether this is from Asia, such as Makassan art, or from European art, and imagery, techniques of art production and modes of visualisation all reflect this.

Arthur Roe was born in Dublin in 1955 and came out with his family as a small child, settling in Melbourne. Collecting was in his genes and as a child he collected football cards, but it was only in the mid-1990s, after visiting Port Jackson Press in Collingwood in Melbourne, that he became interested in collecting art. By about 2000, through an encounter in an exhibition with a painting by Charles Reddington, his eyes were opened to abstraction. At about the same time, he discovered Indigenous art and his art collection started to take shape. Presently the Arthur and Suzie Roe collection contains approximately a thousand items, about two-thirds of which are by Indigenous artists. The collection is rich in the work of Papunya Tula artists, Yirrkala barks, art from the Tiwi Islands and the Torres Strait Islands, with frequently the artists represented by a key or major work or series of works. Other artists in the collection include Elisabeth Cummings, John Peart, Jenny Sages, Aida Tomescu, Ildiko Kovacs, Tony Tuckson, Bruno Leti, Marie Hagerty, Robert Klippel, Lisa Roet and Anthony Pryor. Choices are generally made by the collectors on an aesthetic basis, they frequently fall in love with the work of a particular artist and then acquire the work, sometimes buying a series of works by that artist or ‘trading up’ to the key piece by swapping lesser works to acquire the key work that would best characterise the artist. Collecting for them is a private passion and virtually each piece in the collection has its own story of encounter, discovery and sometimes a prolonged pursuit with the work acquired through instalments over a period of time. The collection is not constrained by medium and paintings jostle for position with sculptures, prints, drawings, ceramics, photographs and digital works.

The Storylines & Songlines exhibition represents less than ten per cent of the whole collection and has been carefully selected by the curators in close consultation with Arthur and Suzie Roe to bring out visual and conceptual synergies amongst the pieces selected. In most instances, the initial choice of a particular artwork has been guided on the basis of visual literacy and other items seem to inevitably fall into place as a process of natural selection.

David Larwill was a Melbourne-based figurative expressionist artist who came to prominence in the context of the Roar Studios group of artists in Fitzroy in Melbourne in 1982, but soon found his own artistic identity in the Australian art scene. In May 1990, Larwill travelled to Alice Springs for the first time with fellow Roar Studios artist Wayne Eager (known as Iggy within the group), where they met up with other Roar Studios artists Mark Schaller and Sarah Faulkner and set up base at the home of John Corker. On that occasion, they spent three months in the Territory with excursions to Palm Valley and onto Aboriginal lands at Kintore, Yuendumu, Haasts Bluff, Papunya, Hermannsburg Mission and Gosse Bluff. During that trip, on a number of occasions, Larwill made friends with Indigenous artists, especially Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, David Mpetyane and Ginger Riley Munduwalawala. Larwill fell in love with the red centre that he was to revisit on numerous occasions throughout his short life. Eager settled in permanently in Alice Springs with his partner and fellow artist, Marina Strocchi.

In this exhibition there are two of Larwill’s large paintings, Fitzroy Island (1985) painted in Launceston in August 1985, where the artist was on a three-week residency at the Cockatoo Gallery and was reminiscing on a two-week driving holiday to Cairns before arriving in Tasmania. The title connects in a tongue-in-cheek manner the holiday pleasures of a small tropical island off the coast of Cairns to the gritty inner city suburb where the Roar adventure began. The other painting, Gentle invention (1994) was painted after his first-hand discovery of Aboriginal art and was painted in Somers, on the Mornington Peninsula, to where the artist had shifted that year. It was exhibited at the Gould Galleries in October of that year and in it the artist extolled the values in Aboriginal communities and contrasted them with the violence and despair of life in New York, where he had recently spent several months, and about which he commented in a number of the other paintings at the exhibition. Larwill in embracing Aboriginal art, does not appropriate it, but responds to its sensibility. Similarly Eager, in his own way, also absorbs the rhythm and palette of the art of the central desert in such paintings as Partita in Grey (2009) and Mesopotamia (2015) included in this exhibition as well as in the more decorative patterning in Strocchi’s Dashwood Creek (2012). Parallels may be drawn with the art of Patrick Mung Mung and Lena Nyadbi found in this exhibition.

Bruno Leti, although born in Italy, has spent virtually all his professional life in Melbourne and many years travelling throughout Australia and internationally. He embraced Indigenous art early in his career and this admiration is reflected throughout his oeuvre. His Thin Eyre (2004) is a superb huge sprawling four-panel oil canvas that is a meditation on Kati Thanda (formerly known as Lake Eyre) as observed from above. Again, although not appropriating any elements of Aboriginal art, the sensibility of aspects of central desert paintings with the shimmering quality of heat appear to assert their presence in the work. One could turn to the art of Doreen Reid Nakamarra included in this exhibition where there exists a parallel sensibility.

Ian Abdulla, a Ngarrindjeri artist, lived all of his life at Cobdolga beside the Murray River where he commenced painting in the late 1980s when he was aged in his forties. The painting in this exhibition, Out at night stealing pumpkins (1999), is one of his classic images of rural life where the caption above proclaims that they had to steal pumpkins for the family to eat because of the high unemployment in the area in the 1950s and 1960s. Although it is a work of an Indigenous artist with its idiosyncratic narrative, the acrylics on canvas and script are some of the elements that the artist has adapted from European art in his work.

The works of non-Indigenous Wedderburn-based artists, working on the fringes of Sydney, including John Peart, Suzanne Archer and Elisabeth Cummings, are convincingly juxtaposed with the paintings of Indigenous artists such as Pepai Jangala Carroll, Wukun Wanambi, Mungurraway Yunupingu and Mithinari Gurruwiwi. There is no argument advanced suggesting any interconnection or interdependency, but one of artists sharing a vision that is frequently based on the land.

The Storylines & Songlines exhibition throughout plays with this sense of a dialectic between Indigenous and non-Indigenous art as one of the qualities that gives contemporary Australian art practice its unique vitality. A leading non-Indigenous sculptor, such as Geoffrey Bartlett in a piece like Silver rain over Halls Gap (1996), not only employs natural materials including River Red Gum (supplemented with galvanised steel, copper, bronze and fibreglass), but there is a sensibility that relates his work to that of Indigenous three-dimensional art. Included in this exhibition are sculptural pieces by Wukun Wanambi, Roderick Yunkaporta, Craig Koomeeta and Simon Norman. Likewise Indigenous potters, including Thancoupie Gloria Fletcher James, Derrick Tjungurrayi, Janet Fieldhouse and Michelle Yateman share sensibilities, techniques and approaches with non-Indigenous potters like Pippin Drysdale and Louise Boscacci.

This exhibition is a triumph of visual intelligence where in a subtle and non-didactic manner a visual argument is advanced for the intrinsic unity of contemporary Australian art that is preserved within its rich diversity of forms.