timeFRAME: Works from the First 3 and last 3 years of the Taylor/Jones Collection

3 September - 6 December 2017

For its second exhibition in 2017, JAHM is privileged to present more than 40 works from the outstanding collection of Canberra couple, Susan Taylor and Peter Jones.

A visit will afford you the unique opportunity to enjoy an exhibition with its very specific focus on non-objective art. This show has been curated by Susan and Peter with great care and attention, and they are personally invested both emotionally and intellectually with each of the works selected.

How different are the works acquired in 2000-2003, the first three years of their collecting journey from those acquired in the last few years? A visit will offer you the opportunity to reflect on their collecting practice and to observe the change in contemporary art practice over the last 20 years. Don’t miss out on this fascinating private collection, never shown in Melbourne before.

The exhibition will again be augmented by complementary works from the JAHM collection upstairs in the Justin apartment.

JAHM SESSIONS

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

CURATORIAL ESSAY

A Living Collection

Essay by Collector Peter Jones

Introduction

This exhibition of works from the collection of Susan Taylor and Peter Jones aspires to open a window on a living collection that is still growing and expanding into new areas and, through sharing their experience, expose some of the underlying considerations and decisions that go into building a collection.

The exhibition is in three parts. Two parts comprise works from the first three years of our collecting (2000-2003, the ‘early selection’) and works from the last three years (2014-2017, the ‘recent selection’). As these periods ‘frame’ the collection over a period of 17 years, timeFRAME seemed an apt exhibition title. A total of 41 works has been included from a collection of over 220 works.

The third part of timeFRAME is a capsule exhibition reprising the first show held in our in-house gallery, Spare Room 33, in April 2013. It presents 20 artist-designed exhibition posters from the avant-garde gallery in Bremerhaven, Germany, the Kabinett für aktuelle Kunst, dating mainly from the 1970’s. There have been 11 further Spare Room 33 exhibitions, all drawn from our collection, and it continues at a rate of three shows per year.

Works in the early selection show our immediate attraction to non-objective art, particularly geometric abstraction. This derived in part from our earlier interest in mid-century modern design. But we were also learning as we went in those first years and we endeavoured to look at as much art as possible to educate ourselves, train our eye and refine our taste. There is an element in the early selection of ‘trying out’ works in different styles and genres, one of which, photography, continues to be a small but important part of our collecting. In choosing to buy such works for our collection – and we conceived of it as a collection before we had reached even half a dozen works – we never varied from our intention to critically discuss and assess what we considered to be the best and strongest works in any exhibition that we visited. As a result, even though we may not have continued to pursue particular genres, the works that we bought at that time generally continue to engage and satisfy us.

Works in the recent selection demonstrate our ongoing commitment to abstraction, but also a preparedness to investigate other forms of artistic expression. This did not involve any revision of our abiding lack of interest in representational and figurative painting, but grew primarily out of our increasing engagement with conceptual art. Focusing on the quality of the artist’s idea, and accepting its primacy, also means accepting that such ideas can be activated in a variety of forms, including found and sculpted objects and quasi-figurative works. As well as continuing to collect particular artists in depth, such as John Nixon and Justin Andrews, we also indentified gaps in the collection, adding new artists and acquiring older works where available and within our means.

The outcome of selecting works for timeFRAME from these two periods is perhaps an overall impression of the collection as more eclectic than a visit to our house would suggest. The middle period of our collecting was predominantly non-objective and abstract, and that remains the spine of the collection.

The third part of the exhibition illustrates another avenue in collecting – the desire to show and make available the collection to others. Collectors do this in various ways: loans to exhibitions, gifts to institutions or establishing a gallery or museum to present the collection to the public (à la JAHM). Our choice was to establish a small gallery space in the guest bedroom of our house, called Spare Room 33, which we created to give exposure to work that doesn’t appear on our walls, principally artists books, works on paper, concrete poetry, exhibition catalogues and ephemera and contemporary jewellery. We aspire for each Spare Room 33 exhibition to be of museum quality, in terms of the selection and presentation of high quality works, the design and production of the invitation cards, and the accuracy and accessibility of the exhibition essays. Ideas for future Spare Room 33 shows have also become powerful engines for our collecting activity, as we will not hold an exhibition until we have assembled a critical mass of quality work.

Early Days

We were relatively late starters on our collecting journey: I was 41 and Susan 31 when we bought our first work, Craig Easton’s Loaded. Neither of us came from art backgrounds and we became adults with no conception of acquiring original art. (The benefit of this may have been that we were not acculturated to believe that a work of art must be ‘of’ something). But we bought our first house in 1996 and, faced with decisions about what to put in it, found ourselves strongly drawn to the clean lined functional forms of mid-century modernism. For several years, we bought furniture, glassware, ceramics and jewellery that reflected that taste. A more direct precursor was a three month visit to Canada and the US in the second half of 1999, where we made it a priority to see as much art and architecture as possible. And one of the friends we stayed with had original art on her walls. If she could do it, why not us?

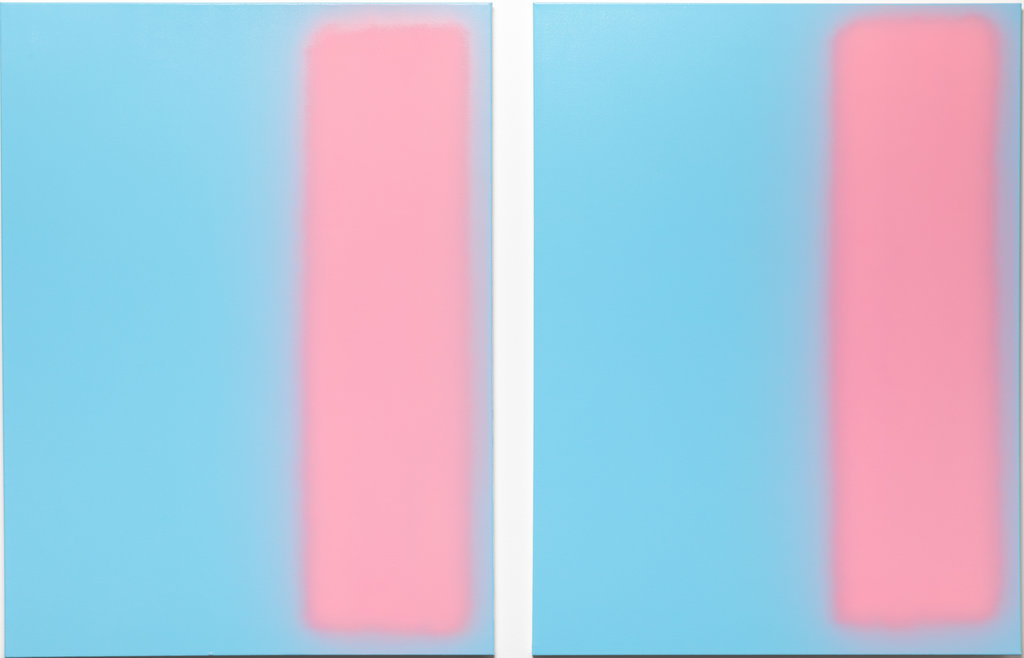

On our return, in the first part of 2000, we made a conscious decision that buying art was something we wanted to do and began visiting the few local galleries in Canberra. We were introduced to Ben Grady Gallery at the time he was showing an exhibition of the New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based painter Craig Easton. Buying Loaded was a bold statement of intent for a first purchase, but one we’d been building to for some time. The painting is large, 12 feet long, and uncompromisingly abstract, comprising two 6 foot panels with two monochrome elements in each panel. We became regular visitors to Ben’s gallery. As well as bringing in artists from interstate, he also showed the work of local Canberra artists such as Marie Hagerty and Andrew Powell. Before Ben closed his gallery in 2002, we bought nine of our first 14 works from him, covering a range of styles, from Easton’s hard-edge abstraction, through the more organic abstractions of Hagerty and Matthew Johnson, to the fragmented and recombined landscapes of Powell and the eerie realism of Tony Lloyd. Seven of those nine works are included in timeFRAME.

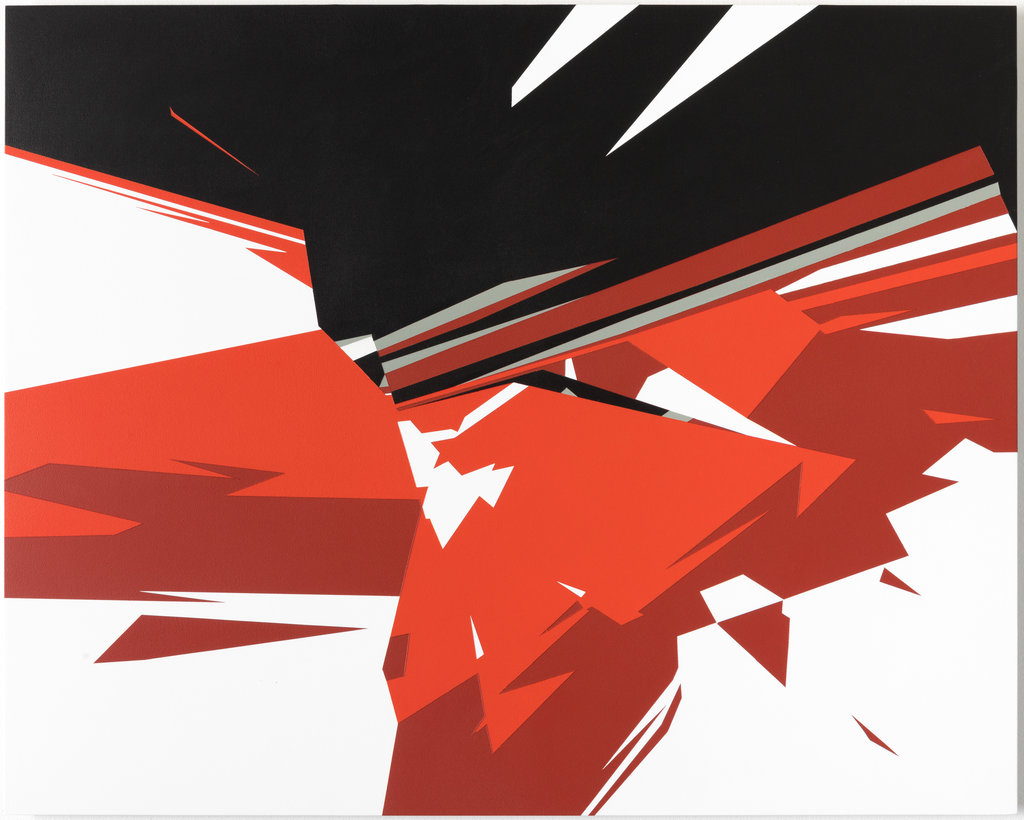

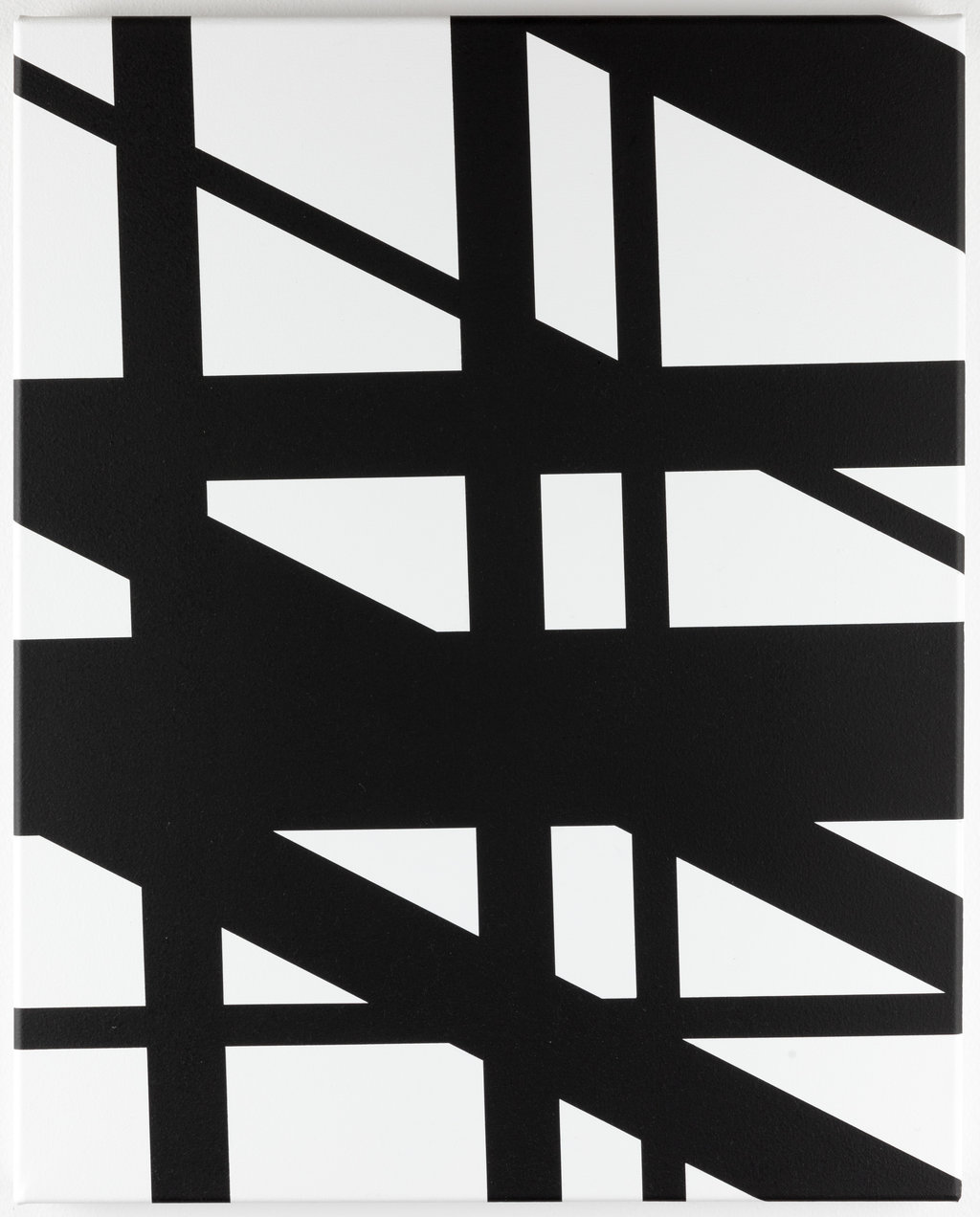

With so few galleries in Canberra, we realised fairly early that we needed to see more art in Melbourne and Sydney. An early landmark was a first visit to Anna Schwartz Gallery in 2001. We were there to meet the contemporary jeweller Susan Cohn, and the visit fortuitously coincided with an exhibition of black and white paintings by Stephen Bram, based on his collaboration with the architect James Brearley, several years previously, in the design of a residence at 6 Penny Lane, South Yarra. We had never heard of Stephen Bram but as soon as we walked in, we knew that this was for us. And even though the show had been up for three weeks and various works had sold, the one that we responded to most strongly hadn’t. It is perhaps a necessary part of collecting to be confident (arrogant?) enough to consider one’s own judgement of a work definitive, irrespective of the views of others. We had little hesitation in buying the painting we considered to be the strongest work in the exhibition. It was the third work in our collection and the commencement of an ongoing admiration for Stephen’s practice.

During this first couple of years, we ingested a large amount of information on Australian art, through conversations with gallerists and artists, visits to exhibitions and reading art books and magazines. Such research led us inevitably to John Nixon. I clearly recall being struck by a picture in Art & Australia of the installation featuring a massive orange monochrome that had won John the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award in 1999, and then feeling intense annoyance at reading David Larwill’s derisive comments on John in another article in the same issue.

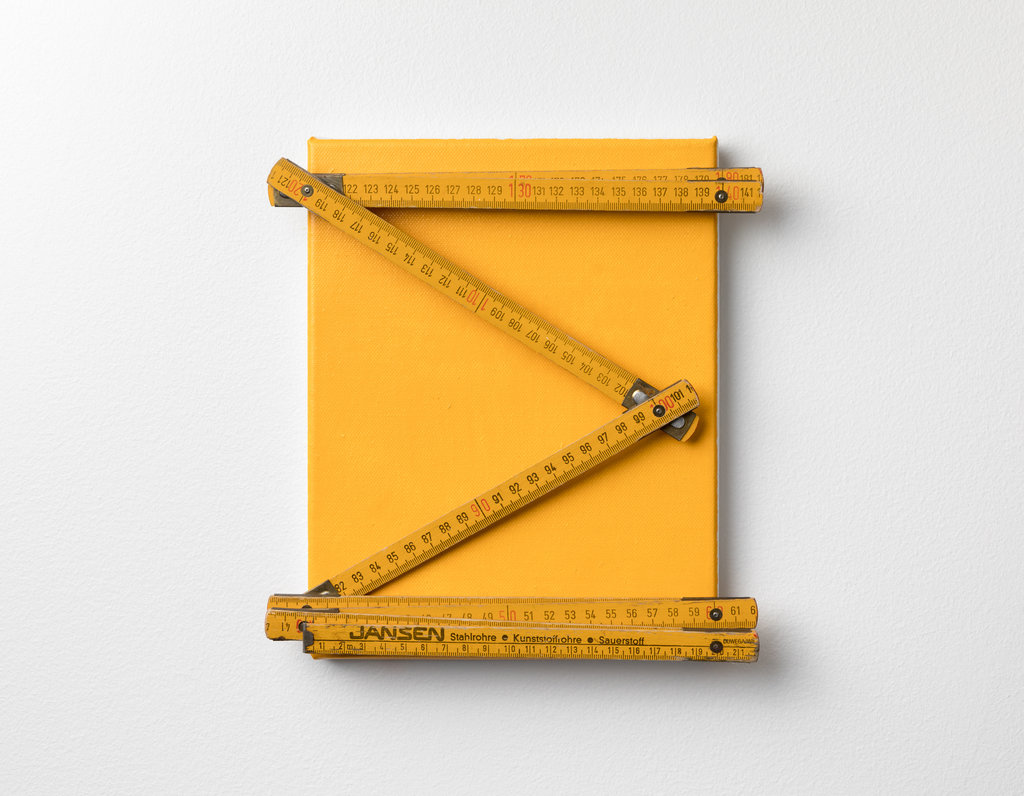

It was a while after that that we heard that John was having an exhibition at Sarah Cottier Gallery, which we went up for and faced the challenge of selecting one work from the many, many on show. The one we picked, Orange Monochrome Construction (with 5 colours), demonstrates John’s incredible command of materials, proportion and colour. Consider, for example, the positioning of a piece of pink dowel against a yellow panel, and the way the topmost piece of wood stops short of the right hand edge, allowing the orange in the upper section to escape and release tension in the work (there is a similar stratagem and effect in Easton’s Loaded). If any one element of this construction was positioned slightly differently, it wouldn’t work. This was the first work of John’s of the 25 that we now have in our collection (there are three others included in timeFRAME; there are no Larwills). Our friendship with John, along with other friendships we have developed with artists whose work we collect, is one of the joys made possible by our engagement with art.

Collecting Now

By 2014, the date at which the second selection of works for timeFRAME commences, we were experienced collectors, buying on average around 15 works a year and actively pursuing an interest in collecting artist books. Due to the time demands of Susan’s retail business, one direction our collecting journey could not go was overseas, excluding us from the various international exhibitions and art fairs. However, abstraction maintains its own international networks of artists and galleries and, through these, we had the opportunity to buy in Australia, in the mid period of our collecting, works by Christoph Dahlhausen, Andreas Exner, Tilman, Jan Maarten Voskuil, Jan van der Ploeg, Guido Winkler and Hans Riedl.

Our love of collecting is directly related to our love of knowledge, and this is at the heart of keeping our collection dynamic and evolving. As the collection grows, each new work brings with it new connections and influences to investigate, which in turn exposes new areas to explore. Seeing lots of exhibitions is also fuel for this process, and is an important antidote to insularity and complacency. Looking at other private collections can also be instructive. I recall our seeing Peter Fay’s collection when it was shown at the NGA in 2004 and, while not liking all of the works, being impressed at how such a variety of high and low art could co-exist within a collection that remained powerful and coherent. Drawing on that example, we began to allow that work that was not initially pleasing to our eye might nevertheless be worthy of deeper consideration, especially if we found ourselves unable to dismiss it from our minds. Indeed, a suspicion of the immediately likeable has become more of a consideration in our collecting, especially when choosing between works.

Another significant influence was our growing interest, from about 2009, in collecting vintage concrete poetry and artist books. By association, this led us to researching and collecting works by the first generation of US and European conceptual artists between 1967 and 1975. Although conceptual art splintered into a variety of practices from around that latter date, and became unfashionable with the rise of neo-expressionist painting and post-modernism in the 1980’s, many of the art practices we see today had their origin in that period of conceptual art. To us, the ideas and wit in those early works seemed as fresh and engaging as when they first appeared.

As a result of this interest, we began to look more at art that demonstrated similar qualities, in terms of the quality of the idea and the rightness of its handing and expression in a particular work. Works by artists such as Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley, Gail Hastings, Robert Rooney and Peter Tyndall have entered the collection in recent times. This tendency has also emerged in our acquisition of objects, such as those in timeFRAME by Tom Buckland, Jacqueline Bradley and Mitchel Cumming. As for John Loane’s work And he rode … , that might at first sight look out of place in our collection, and is as close to abstract expressionism as we have gone, but one of its attractions is the intriguing notion of the disciplined and skilled master print maker overwriting the product of those skills – an etching – and subverting it with the free and unrestrained application of etching ink.

At this point in 2017, we are collecting in five main areas:

works by the artists who we follow closely and collect in depth, e.g. Nixon, Andrews, Hagerty and Peter Vandermark;

filling in gaps and expanding the range of the collection with artists who work in genres we like but have not so far bought (e.g. works by Trevor Vickers, Andrew Christofides and Masato Takasaka were all first works by those artists in the collection), and with historical works, such as Rollin Schlicht’s 1966 screenprints;

identifying young emerging artists, such as Buckland, Anja Loughhead and Patrick Larmour, whose work engages us;

artist books and artefacts of early conceptual art, particularly in support of Spare Room 33 exhibitions; and

contemporary jewellery – a collection motivated by many of the same ideas and tastes as our art collection.

A short word on video art: I have to be frank and admit that, for the longest time, contemporary video art left us cold. We found many works in that genre to be either superficial in their decorativeness or spurious in their alleged profundity, particularly those works that seem to automatically associate filming in slow motion with the sublime. We contrasted these with the spikiness of earlier video art, particularly that which emerged from conceptualism and essentially documented performances, e.g. Mike Parr, Martha Rosler, Ant Farm, Bas Jan Ader. However, things seem to be looking up and we have seen a number of recent works that eschew decoration and use video and sound to activate a strong idea persuasively. Anja Loughhead’s video work Exercises in Repatriation interrogates, with no interceding artifice, the abiding characteristic of Australia as a nation of immigrants. The work caricatures Loughhead’s unsuccessful attempts to make connections with the cultural icons of her Finnish heritage. Sharply resonant, honest, humorous and short, it’s what we’re looking for in a work of video art.

Spare Room 33

As noted in the Introduction, we established Spare Room 33 in 2013 as a space dedicated to showing art that isn’t seen on our walls and would normally be hidden away in storage boxes and map drawers. The twelve exhibitions to date have included themed shows – on artist books, conceptual art catalogues, contemporary jewellery and conceptual photography – and exhibitions of the work of specific artists, including Ian Hamilton Finlay, James Lee Byars, Peter Tyndall, Lawrence Weiner, Peter Downsbrough and Simon Cutts and Stuart Mills.

For timeFRAME, we have chosen to reprise the very first Spare Room 33 exhibition, comprising 20 exhibition posters from the Kabinett für aktuelle Kunst in Bremerhaven, produced between 1972 and 1988. One of the reasons for this choice is that it shows how interesting and engaging exhibition posters can be as collectible artworks in their own right, particularly when the exhibiting artist is involved in their design. Indeed, several of these posters have been included within the catalogue raisonné of the particular artist, Lawrence Weiner and Bas Jan Ader to name two, and others have original photos of the artist’s work tipped in. These posters were screenprinted on the Kabinett premises in editions of around 50 and are quite scarce.

Another reason to reprise this particular show is simply the status of the artists represented – it really is the cream of the European 1970’s avant garde and every artist is worthy of further study. Lest this be thought of as somewhat irrelevant to Australia, many of the artists in the Kabinett posters showed in and visited Australia, e.g. in Sydney Biennales, and a number of important Australian contemporary artists showed and worked in Europe in the 1970’s and 1980’s. The story is more intertwined than a nationalist or isolationist reading of Australian art history usually allows.

Final words

We hope that a close look at the works in timeFRAME, assisted by the contextual information provided in this essay and the notes on the individual works, will fulfil our aim of exposing to visitors to JAHM some of the workings beneath our particular collecting journey, and help demystify the process of building a collection. Collecting art is not as intimidating as those outside the process often think. It requires only the willingness to look at artworks and reflect upon them; to make an initially instinctive connection with an artist or an artwork, and investigate that feeling through (simple) research, discussion and debate; and finally, to make that connection permanent by buying the work.

We want more people to appreciate art and to express that appreciation by buying it, because Australia as a country needs more people to buy art – not commercial prints, not decoration, not knock offs, but genuinely original art that an artist has put their mind and their soul into and has been brave enough to put before the public. Having experienced purchasing a first work, it would be something of a shame not to use that experience as a stepping stone to the next work. We can attest that, from that point on, the rewards are rich and numerous.

Acknowledgements

Susan and I would like to thank Charles and Leah Justin for their vision and fellowship and their generosity in inviting us to show our collection at JAHM. Thanks and gratitude also to Sue Cramer for opening the exhibition. We thank all the artists whose work is represented, and also the many artists who we are privileged to have in our collection but who have not been included by dint of falling outside our date range criteria – we’ll make it up to you! Last but not least, because it is the toughest retail job on earth, we would like to thank the many gallerists who have helped us build the collection over the years through their generous advice and expertise, particularly Ben Grady, David Sequeira, Anna Schwartz, David Pestorius, Sarah Cottier, Charles Nodrum, Geoff Newton, Sabrina Baker, Julian Goddard and Hamish McKay.